Gender bias in language models is nothing new, but here’s the catch: most of the research out there focuses on English. So what about other languages — like Turkish? That’s where our work comes in. In this blog post, we’ll take you through the highlights of our research on gender bias in Turkish word embeddings. Spoiler alert: it’s everywhere — in syntax, semantics, and even the smallest building blocks of Turkish, suffixes.

We all know Turkish is unique. Unlike English, Turkish is an agglutinative language, meaning words are built by adding tons of suffixes. A single word can tell you everything about tense, plurality, possession, and more. This rich morphology makes Turkish super fascinating but also really tricky for language models.

Now, here’s the problem: Most studies on gender bias stick to English or a handful of other languages. In Turkish, the research is super limited. There’s been some work on gender bias in machine translation or Turkish transformer models, but no one’s taken a deep dive into static word embeddings — the OGs of language representations.

We wanted to change that by looking at:

- How biased are Turkish word embeddings?

- How does Turkish morphology affect gender bias?

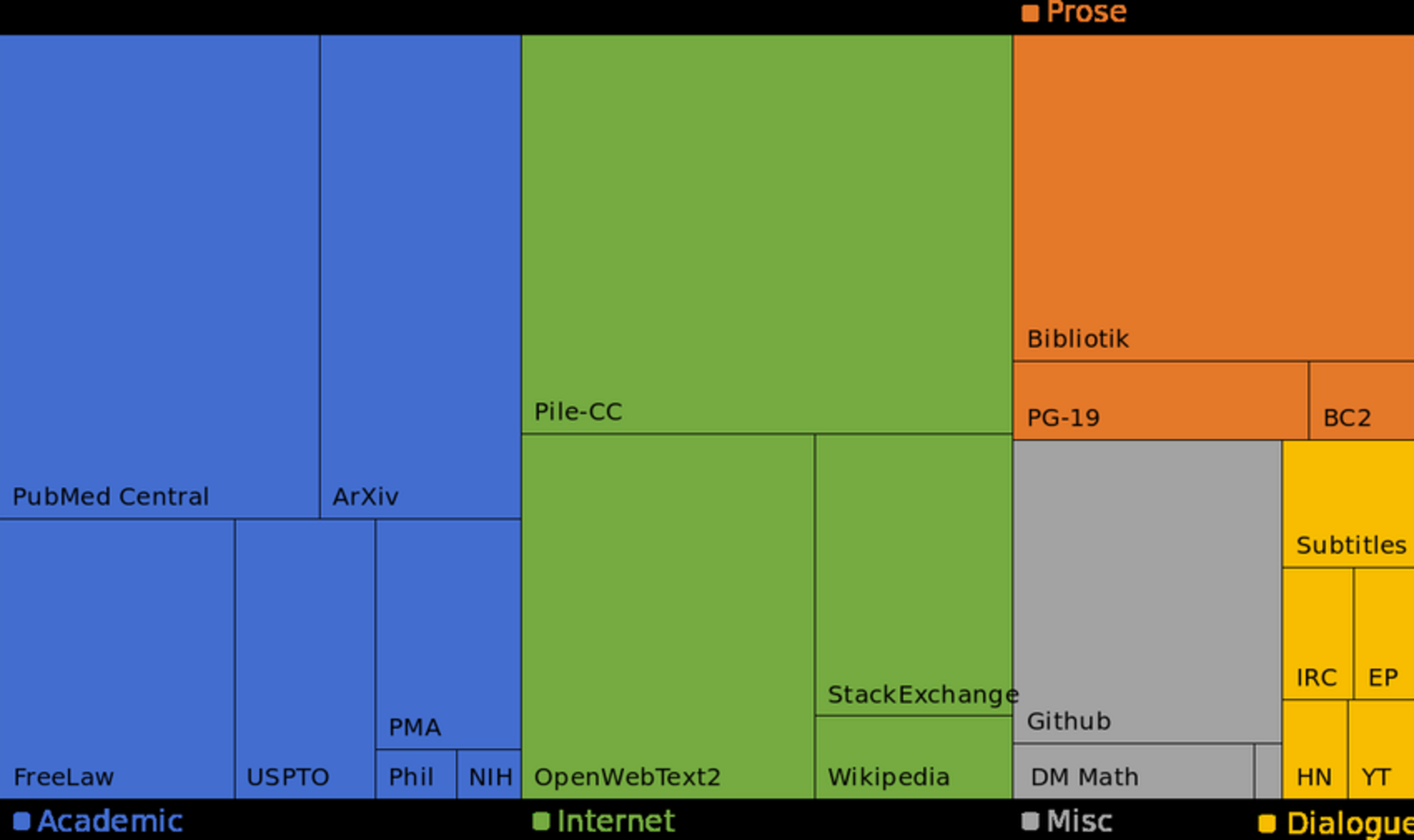

To answer these questions, we trained Floret embeddings (an extension of fastText) on three different datasets:

- Temiz mC4: Cleaned version of Turkish part of CulturaX, a part of BellaTurca.

- Academic Texts: Research papers and abstracts from sources, coming from AkademikDerlem, a part of BellaTurca.

- Medical Texts: Journals focused on healthcare and medicine, coming from AkademikDerlem again.

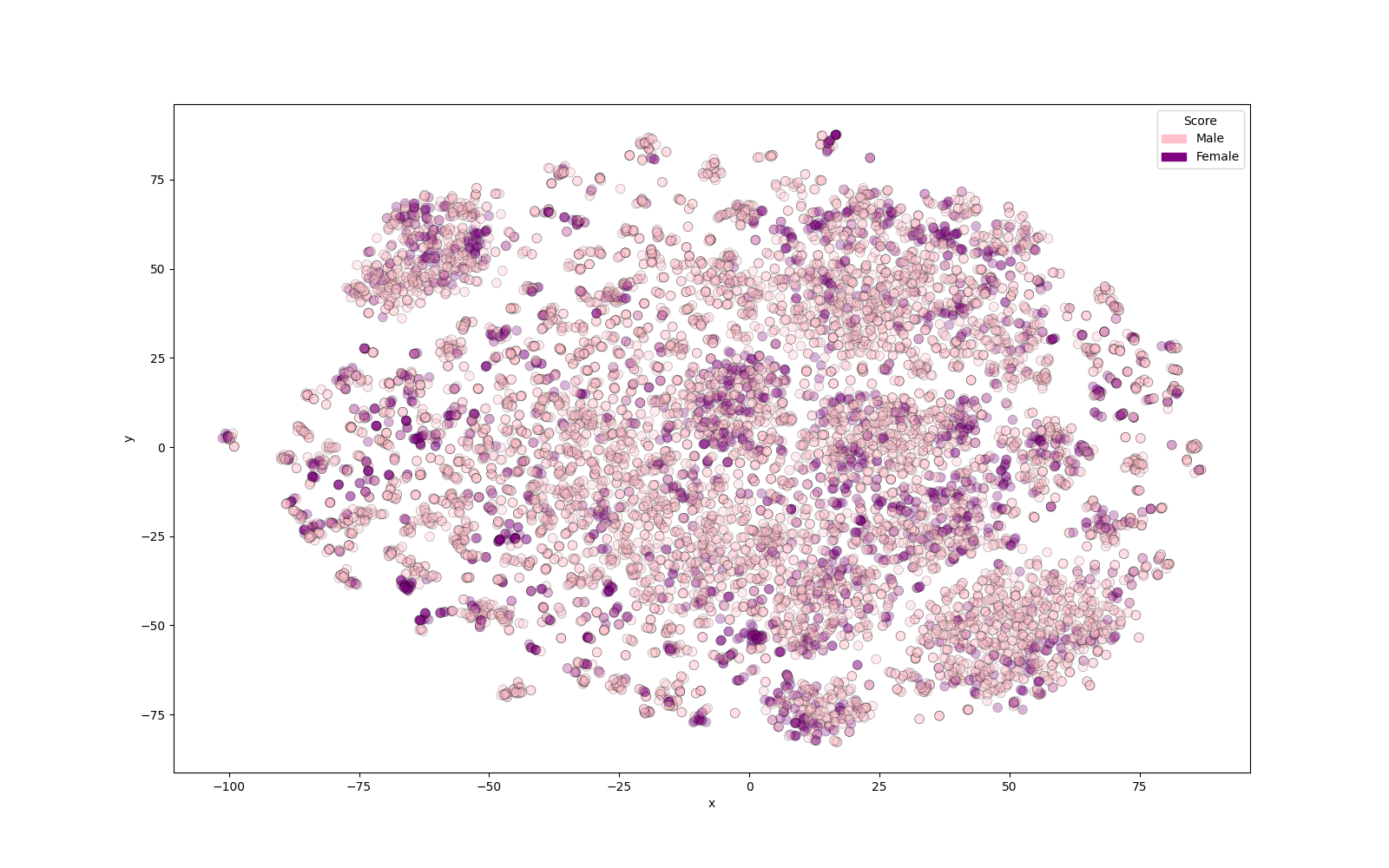

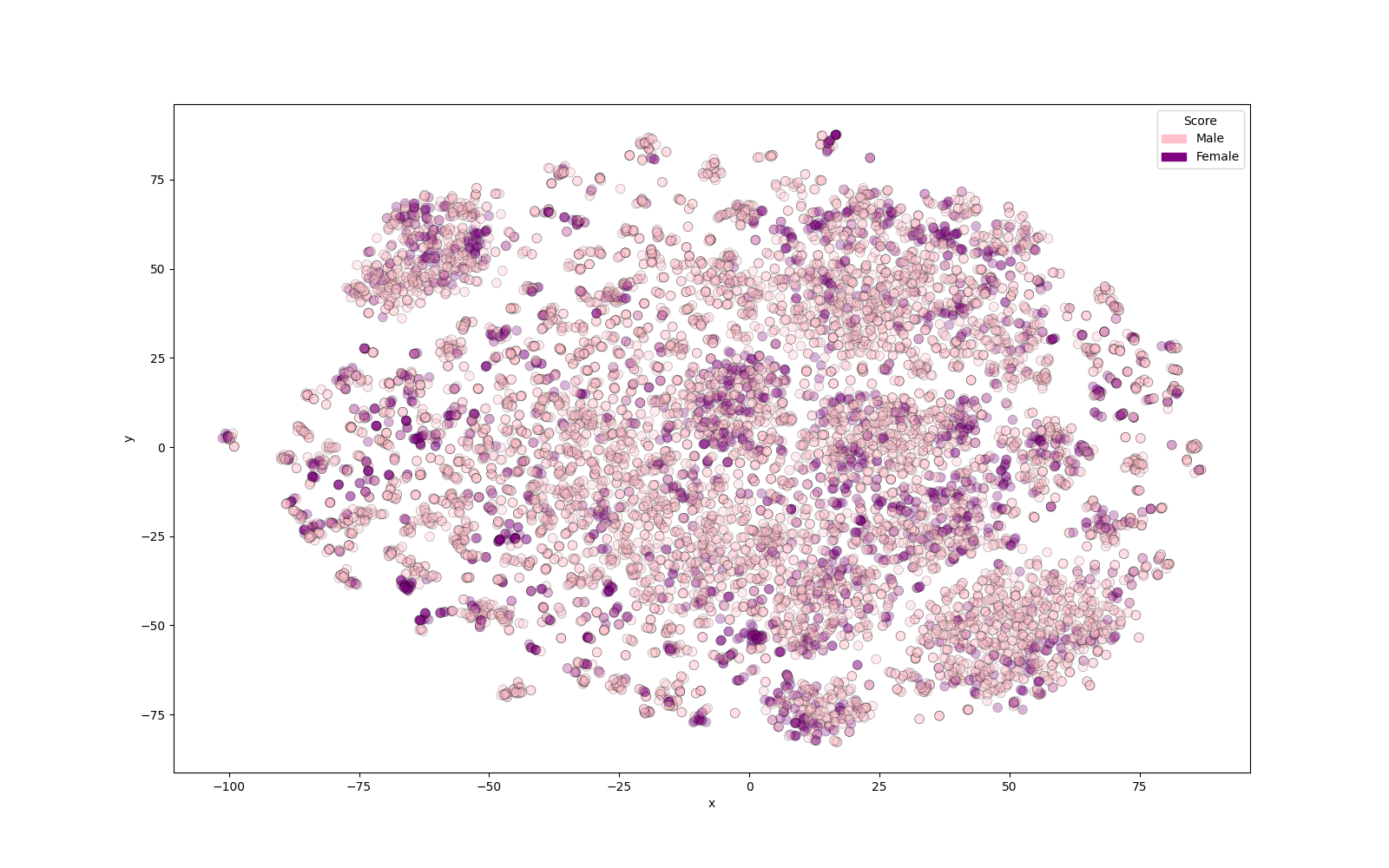

We trained embeddings with a 300-dimensional vector size, capturing both word- and subword-level features to preserve the suffix semantics. Next, for each dataset we calculated the gender of vocabulary words by comparing cosine distance of the word to the words “kadın/woman” and “erkek/man”. Here, the methodlogy is quite different than for English gender studies. Most of the Englisg gender work uses the pronouns “he” and “she” to deduct the gender, however (1) Turkish is a pro-drop language, i.e. we don’t use 3rd personal pronoun often, instead we use a morphological marker in the verb. (2) Even if we wanna use a 3rd pronoun, we only have a single 3rd pronoun “O”, no separate “he”, “she” or “it”. Hence suring word gender calculations, we rely on semantic distance.

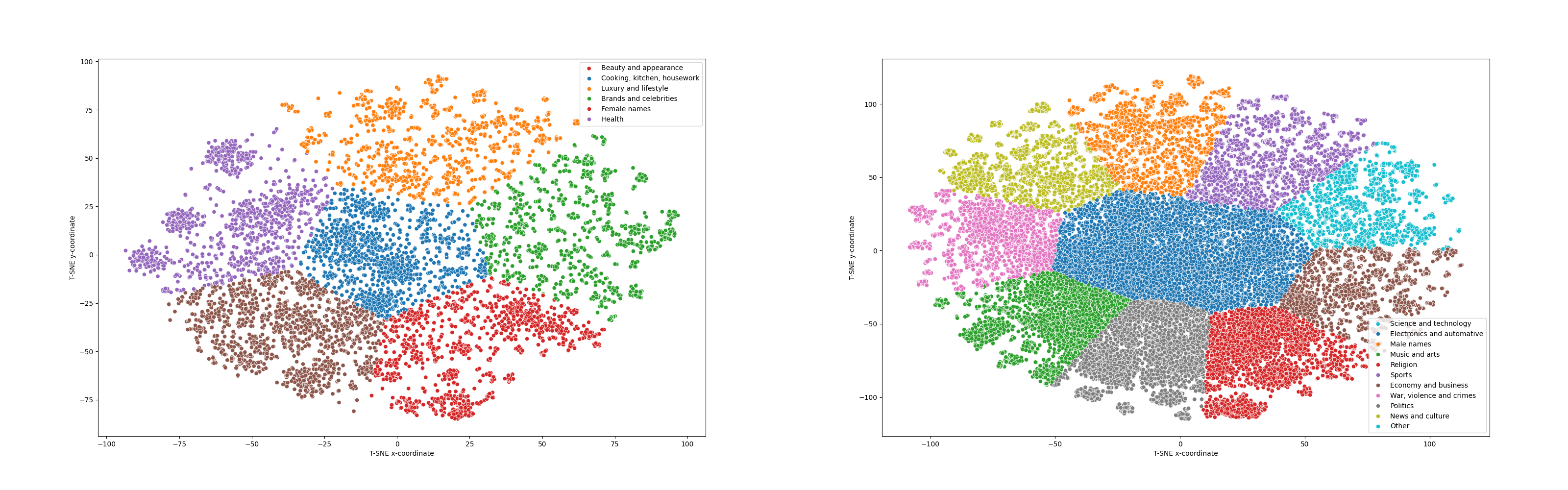

The second and the most crucial part of this study is to classify word genders by POS tags. In the second leg of study, again per dataset we calculate POS of each word in the corpus and count female/male words ratio per POS tag.

The Shocking Results

Here’s what we found:

Masculine Defaults Everywhere

Across all datasets, most words were associated with masculinity. For example, in the web crawl corpus, 87% of the vocabulary leaned masculine, while only 13% was feminine. And it’s not just nouns — verbs, adjectives, and even adverbs showed similar trends.

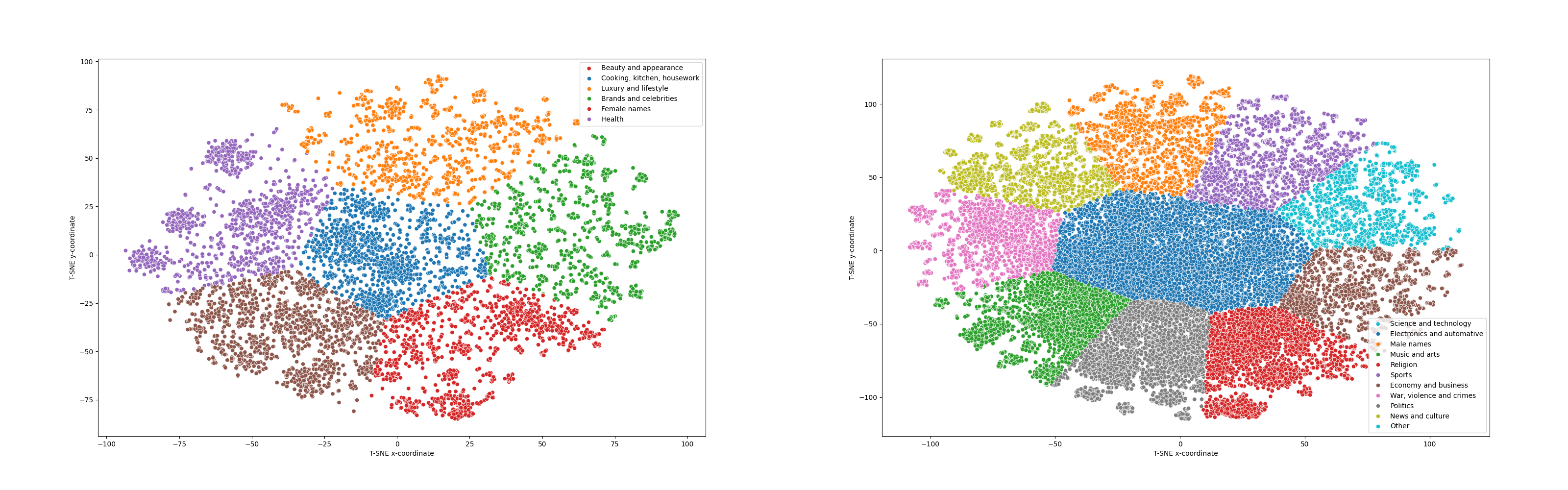

Examples of feminine words:

- Beauty-related: güzellik (beauty), makyaj (makeup), çiçek (flower).

- Domestic words: ev (home), temizlik (cleaning).

- Proper nouns: Female names like Burcu, Ayşen and Maria.

Examples of masculine words:

- Professions: doktor (doctor), mühendis (engineer), yönetici (manager).

- Sports: tenis (tennis), voleybol (volleyball).

- Abstract concepts: bilim (science), liderlik (leadership).

Sadly, these biases reflect real-world stereotypes, where men dominate professions, leadership roles, and sports, while women are associated with beauty, family, and domesticity.

Gender Bias in Syntax

We also looked at different parts of speech and found gender bias everywhere.

- Verbs: Masculine verbs were common, covering general actions like gitmek (to go) and yapmak (to do). Feminine verbs were few and often tied to stereotypical roles, like süslenmek (to dress up) and güzelleşmek (to become beautiful).

- Nouns: Feminine nouns were mostly proper names or gendered loan words like tanrıça (goddess) and kraliçe (queen). In contrast, masculine nouns spanned professions, technology, and abstract concepts.

The Role of Suffixes

Here’s where it gets even more interesting: Turkish suffixes can change a word’s gender!

- Plural Suffix (-lAr): Often shifts masculine words to feminine. For example, kitap (book, masculine) becomes kitaplar (books, feminine).

- Negative Marker (-mA): Can flip the gender of verbs. For example, üretmek (to produce, feminine) becomes üretmemek (not to produce, masculine).

- Passive Voice: The passive voice changes masculine verbs into feminine verbs, but not the other way around e.g. okumak (M) - okunmak (F) to read vs to be read.

- Nominal->Verb Derivators: Suffixes in this category typically shift feminine nouns to masculine verbs, as in the example sendika (F) - sendikalaşma (M) (labor union-unionization).

This shows that morphology plays a huge role in gender bias for Turkish, making it unique compared to English. One noteworthy point is that verbs are often perceived as masculine, likely because the concept of action is associated with masculinity. In patriarchal societies, women are oppressed and relegated to passive roles, while men are expected to perform actions. Consequently, verbs are seen as masculine, and the suffixes that transform nouns into verbs are also viewed as masculine. Similarly, the passive voice reflects these gendered dynamics, as the passive roles assigned to women are mirrored in the suffixes used to form it.

Domain Differences

The level of gender bias varied depending on the dataset:

- Web Crawl Data: The most biased dataset, with strong masculine associations.

- Academic Texts: Slightly more balanced, thanks to scientific and formal vocabulary.

- Medical Texts: Had more feminine words, like jinekolojik (gynecological) and klinik (clinic), but still leaned masculine overall.

Gender bias in word embeddings isn’t just an academic problem, it can have real life consequences. For Turkish, this is even more critical because the language’s rich morphology makes it harder to detect and address bias.

What’s Next?

Our study is just the beginning. Here’s what we hope to see in future research:

- Bias Mitigation: Developing techniques to reduce gender bias in Turkish embeddings.

- Linguistic Studies: Exploring how morphology influences bias in other agglutinative languages.

- Better Datasets: Building gender-balanced corpora for training fairer models.

If you’re curious about our full methodology or want to play with the embeddings yourself, check out our GitHub repo and even better read the publication.