Bir varmış; bir yokmuş / Evvel zaman içinde / Kalbur saman içinde / Develer tellal iken / Pireler berber iken / Ben dedemin beşiğini tıngır mıngır sallarken…

Once upon a parse tree — and not the flimsy kind, but the kind that could bench-press a dragon — we pointed spaCy’s Turkish models at a stack of masals and asked a simple question: who did what to whom, when, and with how much -mış energy? Forget NER glamour. This is the gritty, syntactic underbelly of fairy tales: clause chains that sprint through forests, passives that hide culprits behind enchanted doors, causatives that make princes make others do things, and quotatives where everyone keeps saying “dedi” like it’s a spell. We’ll wrangle “Bir varmış, bir yokmuş” into solid sentence boundaries, stitch subject–verb–object frames out of scrambled word order, and pin dialogues to actual speakers without summoning a demon. Bring your suffix lore, your discourse markers, and your best parser face — we’re mining Turkish fairy tales for structure, not vibes.

Before we dive into dragons and dialog, a quick map of the forest: Turkish parse trees are where agglutination meets free-ish word order and politely ignores your English instincts. One verb can carry tense, aspect, mood, polarity, person, voice, and evidentiality on its back like a mule with seven saddlebags, while subjects take coffee breaks offstage thanks to pro-drop. Case endings do the heavy lifting for roles (accusative for definite victims, dative for goals, ablative for exits), so dependency edges matter more than token order; “dev-i Keloğlan yendi” and “Keloğlan dev-i yendi” collapse to the same who-beat-whom frame if your parser keeps its cool. Expect rich non-finite action—-ip, -ince, -meden—braiding clause chains; participial relatives (-dik, -ecek, -an) nesting inside NPs like Russian dolls; and voice flips (passive, causative, reflexive) that rewrite agency without changing the verb’s lemma. In other words: Turkish syntax is dense, expressive, and delightfully hackable—as long as you read the morphology and trust the dependencies more than the word positions.

So how do we bottle that chaos into structure? We start by tracing clause chains—the verb-to-verb railways that power fairy-tale tempo—then peel off their satellites with subordination to see what happened, when, and why. From there, we zoom into embeddings: ccomp and xcomp that tuck plans, promises, and prophecies inside larger sentences. Because plot is mostly people talking, we’ll wire up quotation and speech patterns, matching every “dedi” to an actual speaker. Lists are the drumbeat of masals, so we’ll map coordination patterns to catch the famous “üç” rhythm in nouns and verbs alike. Finally, we’ll merge epithets with names via apposition and renaming—so “Şahmaran, yılanların şahı” is one entity, not two—before exporting everything into clean, queryable structures.

Before all the code, we’ll do some pips to prepare our setup. The second line is gonna install the spaCy model tr_core_news_trf from the official spaCy Turkish models Hugging Face repo:

pip install -U spacy pandas matplotlib

pip install https://huggingface.co/turkish-nlp-suite/tr_core_news_trf/resolve/main/tr_core_news_trf-1.0-py3-none-any.whl

pip install datasets

After making the pips, now we can go ahead and download our dataset MasalMasal from Turkish NLP Suite HF repo:

from datasets import load_dataset

dataset = load_dataset("turkish-nlp-suite/OzenliDerlem", "MasalMasal", split="train")

texts = dataset["text"] # the dataset only has a single field, text

len(texts)

2621

texts[50]

Çok uzak diyarlarda çok güzel bir kelebek varmış. Bu kelebeğin kanatları rengarenk desenlerle doluymuş. Pembe, mavi, sarı, yeşil... Bu kelebek çok neşeliymiş. Çiçeklere konar, şarkılar söyleyerek uçarmış. Her sabah güneş doğduğunda gezintiye çıkar, akşam olduğunda bir çiçeğe konar ve mışıl mışıl uykuya dalarmış. Bir gün, bu güzel kelebek yine gezintiye çıkmış ve çok yorulmuş. Güneş batınca uyumak için kendine büyük güzel bir çiçek bulmuş. Bu çiçeğin üstüne kıvrılmış ve yıldızların altında uykuya dalmış. Sabah olduğunda, bir vızıltıyla uyanmış. Vızzz...vızzzz. Kelebek gözlerini açmış ve karşısında bir arı görmüş. Arıdan çok korkmuş ve telaşla uçmaya çalışmış. Ama o da ne! Kelebeğin kanadı çiçeğe yapışmış. Kelebek uçamıyormuş. Daha sonra arı kelebeğe doğru yaklaşmış. Oysa ki kelebeğin kanadı arının topladığı bala yapışmış. Kelebek bir kanadını, arı da topladığı balı kaybetmiş. Kelebek ağlamaya başlamış. Arı bu duruma çok üzülmüş. Kelebeğe yardım etmek istiyormuş. Kelebekle konuşmuş ''Kanadının bala yapışması benim suçum. Özür dilerim. Balı orada bırakmamalıydım. Bu yüzden sana yardım etmek istiyorum.'' Demiş. Kelebek; ''Bana nasıl yardım edebilirsin ki?'' diye sormuş üzgün bir sesle. Arı kelebeği sırtına almış ve nereye uçmak isterse artık onu oraya uçuracağını söylemiş. Kelebek ve arı sonsuza dek beraber uçarak tüm güzellikleri keşfetmişler.

Also let’s import spaCy and load our Turkish spaCy model:

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("tr_core_news_trf")

The first linguistic phenomena for us is clause chaining and parataxis. Clause chaining and parataxis are the turbo boost of Turkish storytelling: instead of nesting clauses under one another, the prose lines up full events back-to-back—çıktı, kapadı, bekledi—letting commas, ve, and markers like sonra do the pacing. Each clause stands on its own feet, sharing subjects by context (thanks, pro-drop) and keeping the narrative sprinting. This is different from subordination, where a clause bends to another’s purpose—gelince, -meden, -ken—to explain when, why, or how. In chaining, clauses are peers; in subordination, they’re satellites. For fairy tales, that peer-to-peer rhythm delivers clear beats and a spoken, drumlike cadence.

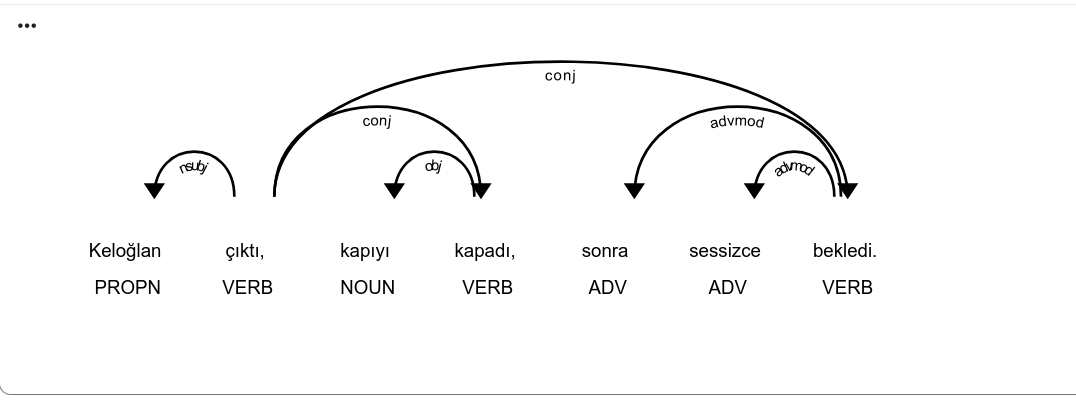

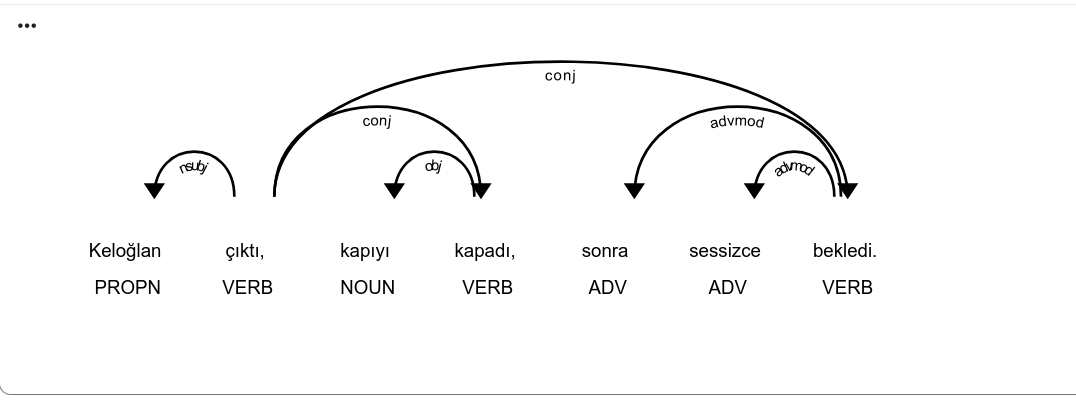

Here’s an example for us, the sentence “Keloğlan çıktı, kapıyı kapadı, sonra sessizce bekledi.”. Let’s look for clues of chaining in the dependency tree:

sent = "Keloğlan çıktı, kapıyı kapadı, sonra sessizce bekledi."

doc = nlp(sent)

for token in doc:

print(token, token.dep_, token.head)

Keloğlan nsubj çıktı

çıktı ROOT çıktı

, punct kapadı

kapıyı obj kapadı

kapadı conj çıktı

, punct bekledi

sonra advmod bekledi

sessizce advmod bekledi

bekledi conj çıktı

. punct bekledi

Here for every token we printed the syntactic head in the dependency tree and the dependency relation in between. Looks like some chaining happening, for more understanding let’s visualize the dependency tree with displaCy. Here is the code and the dependency tree generated is displayed in the first figure of the page:

from spacy import displacy

displacy.render(doc, style='dep', jupyter=True, options={'distance': 90})

Looking at the dependency tree , the main verb “çıktı” is chained to “kapadı” and “bekledi” by the relation “conj”, which is conjunction. Conjunction can be made by commas or conjuncts such as ve. We’re also looking for some discourse connectors such as önce, sonra. Let’s make the code and dissect it afterwards:

DISCOURSE_MARKERS = {"sonra", "derken", "nihayet", "o", "ondan", "meğer"} # we can expand more

def is_verbal_head(tok):

return tok.pos_ == "VERB"

def chain_from_root(root):

# BFS over conj edges but keep only verbal heads

chain = set([root])

queue = [root]

while queue:

cur = queue.pop()

# outgoing conj (siblings)

for child in cur.children:

if child.dep_ == "conj" and is_verbal_head(child):

if child not in chain:

chain.add(child)

queue.append(child)

# incoming conj (if current is a conjunct, climb to its head and collect siblings)

if cur.dep_ == "conj" and is_verbal_head(cur.head):

head = cur.head

if head not in chain:

chain.add(head)

queue.append(head)

return sorted(chain, key=lambda t: t.i)

def verb_chain_features(sent):

# Find candidate roots (some sentences have multiple due to punctuation/ocr)

roots = [t for t in sent if t.dep_ == "ROOT" and is_verbal_head(t)]

chains = []

seen = set()

for r in roots:

chain = chain_from_root(r)

# De-duplicate overlapping chains by the set of token ids

key = tuple([t.i for t in chain])

if key in seen:

continue

seen.add(key)

# Collect discourse markers attached to last verb in chain or present in sent

markers = [t.text for t in sent if t.dep_ == "advmod" and t.lemma_.lower() in DISCOURSE_MARKERS]

# Optionally, gather per-verb adverbs/objects

verbs = []

for v in chain:

verbs.append({

"i": v.i,

"text": v.text,

"lemma": v.lemma_,

"morph": v.morph.to_dict(),

"advmods": [c.text for c in v.children if c.dep_ == "advmod"],

"objects": [c.text for c in v.children if c.dep_ in {"obj", "iobj"}],

"obl": [c.text for c in v.children if c.dep_ == "obl"]

})

chains.append({

"verbs": [v.text for v in chain],

"markers": markers,

"verbs_detail": verbs

})

# Optional: split a chain at strong punctuation between verbs (commas usually keep chain; semicolons split)

return chains

The function starts by finding the sentence’s verbal ROOT, because in dependency parses the main finite verb anchors the clause. From that root, it builds a chain by walking conj edges: any sibling verb connected via conj is added, and if a verb is itself a conjunct, the code also climbs to its head to gather all peers—this bidirectional walk ensures we capture çıktı, kapadı, bekledi even if the parser attached them asymmetrically. Once the set of verbs is collected, it’s sorted by token index to restore narrative order. For each verb in the chain, the code “decorates” it with local dependents—advmod (e.g., sonra, sessizce), objects (obj/iobj), and obliques (obl)—so you can later analyze pacing and argument structure per step. In parallel, it scans the sentence for discourse markers (like sonra, derken) to characterize tempo. Finally, it packages each chain as a small record with the verb texts and their details, and it guards against duplicates by hashing token indices, since some sentences can yield overlapping chains when multiple roots or parse quirks occur.

Let’s feed our sentence to our function:

for sent in doc.sents:

print(verb_chain_features(sent))

[{'verbs': ['çıktı', 'kapadı', 'bekledi'], 'markers': ['sonra'], 'verbs_detail': [{'i': 1, 'text': 'çıktı', 'lemma': 'çık', 'morph': {'Aspect': 'Perf', 'Evident': 'Fh', 'Number': 'Sing', 'Person': '3', 'Polarity': 'Pos', 'Tense': 'Past'}, 'advmods': [], 'objects': [], 'obl': []}, {'i': 4, 'text': 'kapadı', 'lemma': 'kapa', 'morph': {'Aspect': 'Perf', 'Evident': 'Fh', 'Number': 'Sing', 'Person': '3', 'Polarity': 'Pos', 'Tense': 'Past'}, 'advmods': [], 'objects': ['kapıyı'], 'obl': []}, {'i': 8, 'text': 'bekledi', 'lemma': 'bekle', 'morph': {'Aspect': 'Perf', 'Evident': 'Fh', 'Number': 'Sing', 'Person': '3', 'Polarity': 'Pos', 'Tense': 'Past'}, 'advmods': ['sonra', 'sessizce'], 'objects': [], 'obl': []}]}]

Compare it to a quite flat sentence’s output:

text = "ben de gittim."

doc = nlp(text)

for sent in doc.sents:

print(verb_chain_features(sent))

[{'verbs': ['gittim'], 'markers': [], 'verbs_detail': [{'i': 2, 'text': 'gittim', 'lemma': 'git', 'morph': {'Aspect': 'Perf', 'Evident': 'Fh', 'Number': 'Sing', 'Person': '1', 'Polarity': 'Pos', 'Tense': 'Past'}, 'advmods': [], 'objects': [], 'obl': []}]}]

There’s no chain in this flat sentence, compared it to the first sentence. So the rule is simple, if the length of the chain is greater than 1, we have a chaining sentence. Let’s count how many of those sentences occur in 10 tales of our corpus:

def count_chained_sentences(texts) -> int:

count = 0

for doc in nlp.pipe(texts, disable=[]):

for sent in doc.sents:

chains = verb_chain_features(sent)

if any(len(c["verbs"]) > 1 for c in chains):

count += 1

return count

texts = texts[50:60]

count_chained_sentences(texts)

53

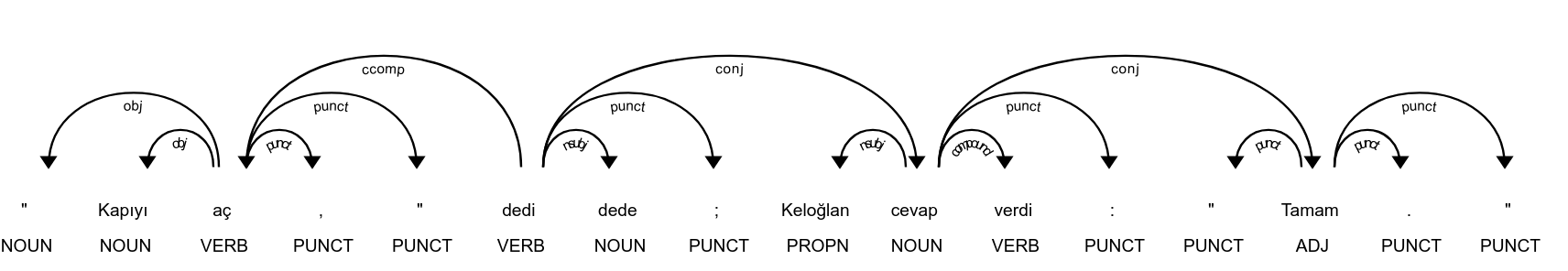

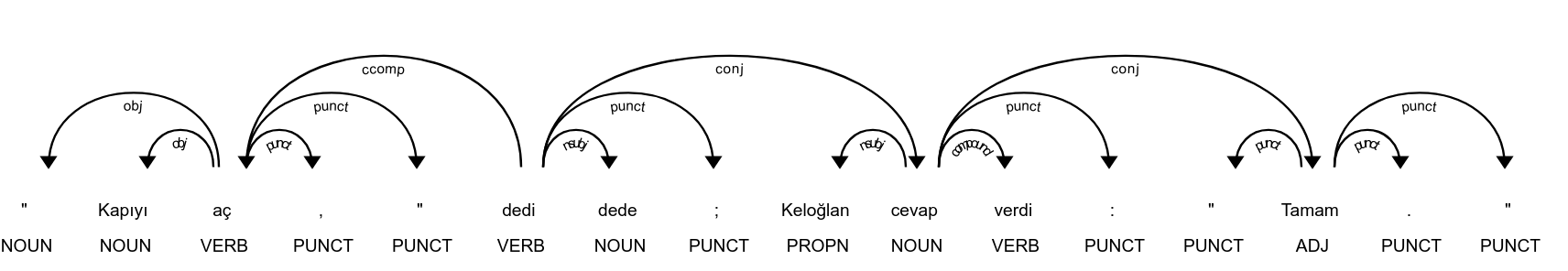

Great, right? We told you fairy tales are full of syntactic sugar. Next phenomena of this article is quotation and speech constructions, as in the sentence "Kapıyı aç," dedi dede; Keloğlan cevap verdi: "Tamam.". Quotation and speech constructions encode who says what and how, using a quoted segment plus a reporting clause with a speech verb. In Turkish, direct speech is typically enclosed in quotes and anchored by verbs like demek, söylemek, sormak, fısıldamak, bağırmak, often with adverbs or manner cues, and the speaker as a noun phrase: “Kapıyı aç,” dedi dede. The reporting clause can precede, follow, or split the quote; punctuation and intonation carry much of the structure. You’ll also see diye introducing quoted content or intentions (“Korkmasın diye fısıldadı”) and ki after demek for content clauses (“Dedi ki kapı kilitli”). In dependency terms, treat the quoted span as a content unit attached to the SAY-verb (ccomp/parataxis depending on the parser), link the speaker NP to the verb (nsubj), and watch for multiple quotes coordinated to one reporting verb. This mapping lets you attribute lines reliably, even with pro-drop and free-ish word order.

Looking for the clues, let’s visualize the dependency tree as exhibited in the second figure of the page. In this example, the parser gives us two reporting anchors and two quoted contents, tied together by coordination and punctuation. The first anchor is dedi (ROOT) with the speaker dede as its nsubj. Its content is the clause headed by aç, attached via ccomp, and that clause is clearly delimited by opening and closing quote tokens plus a following comma: “Kapıyı aç,”. Notice that Kapıyı is the obj of aç, and the leading quote mark is (somewhat noisily) attached as obj to aç as well, while the trailing quote and comma are punct dependents—typical quirks you should tolerate. After the first speech event, a semicolon punct attaches to dedi but simply separates two coordinated reporting clauses. The second anchor is cevap, which is a conj dependent of dedi: this captures the narrative sequence “dedi; … cevap verdi.” The speaker here is Keloğlan (nsubj of cevap), and the light verb verdi appears as compound under cevap—so normalize this as the multiword speech verb cevap vermek. A colon punct on cevap cues that its quote follows. Indeed, the second quoted content is the single-word Tamam, tokenized as a conj attached to cevap, wrapped by quote marks recognized as punct on either side; in practice, you can treat the quoted span beginning at the opening quote before Tamam and ending at the closing quote after Tamam as the content of cevap. Putting it together: event 1 = {speaker: dede, verb: dedi, quote: “Kapıyı aç”}; event 2 = {speaker: Keloğlan, verb: cevap verdi, quote: “Tamam”}. The key signals you’d generalize from this tree are: (1) a speech verb head (demek or a compound like cevap+vermek) with an nsubj speaker; (2) a content clause linked by ccomp or, for very short quotes, a nearby span enclosed by quotation marks and attached via ccomp/conj; (3) tolerance for intervening punctuation (, ; :) and coordination (conj) connecting multiple reporting verbs into one sequence. Below goes the code snippet, and we feed our example sentence:

SPEECH_LEMMAS = {

"de", "söyle", "sor", "yanıtla", "cevapla",

"fısılda", "bağır", "seslen",

"açıkla", "anlat"

}

# Some speech is expressed as light-verb constructions. We'll normalize a few:

LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS = {

# head_lemma -> allowed light-verb lemmas that may appear as child or parent

"cevap": {"ver"},

"yanıt": {"ver"},

"söz": {"söyle", "de"}, # "söz söyledi" (rare), "söz dedi" (noisy)

}

QUOTE_CHARS = {'"', "“", "”", "„", "‟", "«", "»", "‚", "‘", "’", "'"}

def is_quote_token(tok):

return tok.text in QUOTE_CHARS

def is_reporting_head(tok):

# Plain speech verbs

if tok.pos_ in {"VERB", "AUX"} and tok.lemma_ in SPEECH_LEMMAS:

return True

# Noun heads in light-verb constructions (e.g., "cevap" with child "verdi")

if tok.lemma_ in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS:

for c in tok.children:

if c.lemma_ in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS[tok.lemma_] and c.pos_ in {"AUX", "VERB"}:

return True

# Sometimes the light verb is the head and the noun is a child

if tok.head.lemma_ in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS.get(tok.head.lemma_, set()):

return True

# Light verb as head (e.g., "vermek") with a noun like "cevap" as child

if tok.lemma_ in {lv for s in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS.values() for lv in s}:

for c in tok.children:

if c.lemma_ in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS and tok.lemma_ in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS[c.lemma_]:

return True

return False

def normalize_reporting_verb(tok):

# Return a readable label like "demek" or "cevap vermek"

if tok.lemma_ in SPEECH_LEMMAS:

return tok.lemma_

# Noun head + light verb child

if tok.lemma_ in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS:

for c in tok.children:

if c.lemma_ in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS[tok.lemma_]:

return f"{tok.lemma_} {c.lemma_}"

# Sometimes light verb is the head

if tok.head.lemma_ in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS[tok.lemma_]:

return f"{tok.lemma_} {tok.head.lemma_}"

# Light verb head + noun child

if tok.lemma_ in {lv for s in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS.values() for lv in s}:

for c in tok.children:

if c.lemma_ in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS and tok.lemma_ in LIGHT_VERB_CONSTRUCTIONS[c.lemma_]:

return f"{c.lemma_} {tok.lemma_}"

return tok.lemma_

def get_speaker(tok):

# Prefer explicit nsubj

subs = [c for c in tok.children if c.dep_ == "nsubj"]

if subs:

# Make subtree into a span-safe string

nodes = list(subs[0].subtree)

start = min(t.i for t in nodes)

end = max(t.i for t in nodes) + 1

return tok.doc[start:end].text

# If conjunct reporting verb, inherit nsubj from the head if present

if tok.dep_ == "conj" and tok.head is not tok:

head_subs = [c for c in tok.head.children if c.dep_ == "nsubj"]

if head_subs:

nodes = list(head_subs[0].subtree)

start = min(t.i for t in nodes)

end = max(t.i for t in nodes) + 1

return tok.doc[start:end].text

return None

def expand_to_quoted_span(anchor, doc):

# Find closest opening and closing quote around a token index, within the same sentence

sent = doc[anchor].sent

# Search left for opening quote

left = None

for i in range(doc[anchor].i, sent.start - 1, -1):

if is_quote_token(doc[i]):

left = i

break

# Search right for closing quote

right = None

for i in range(doc[anchor].i, sent.end):

if is_quote_token(doc[i]):

right = i

# ensure right is after left if both exist

if left is not None and right > left:

break

if left is not None and right is not None and right > left:

return left, right

return None

def quoted_text_between(span, doc):

start, end = span

# exclude the quote tokens themselves

inner = doc[start+1:end]

# strip trailing/leading punctuation like commas inside quotes

text = inner.text.strip()

if text and text[-1] in {",", ";", ":"}:

text = text[:-1].rstrip()

return text

def content_heads(tok):

# Heads that likely represent the quoted content

heads = []

for c in tok.children:

if c.dep_ in {"ccomp", "parataxis"}:

heads.append(c)

# Sometimes very short quotes are attached via conj or appos-like patterns; consider nearest token in quotes

return heads

def nearest_quoted_span_for_tok(tok, doc):

# Prefer spans on the side suggested by punctuation:

# - if there is a colon child, prefer right side; else check both

has_colon = any(c.text == ":" and c.dep_ == "punct" for c in tok.children)

if has_colon:

span = expand_to_quoted_span(tok.i + 1, doc)

if span:

return quoted_text_between(span, doc)

# General fallback

span = expand_to_quoted_span(tok.i, doc)

if span:

return quoted_text_between(span, doc)

return None

def get_quote_for_reporting_verb(rv):

sent = rv.sent

doc = rv.doc

def tokens_right_of(tok):

# yield tokens strictly to the right of tok within the same sentence

for i in range(tok.i + 1, sent.end):

yield doc[i]

def first_quoted_span(tokens_iter):

# find first opening quote token, then collect until the next quote token

open_i = None

for t in tokens_iter:

if t.text in QUOTE_CHARS:

open_i = t.i

break

if open_i is None:

return None

# collect inner tokens until closing quote

inner_tokens = []

for j in range(open_i + 1, sent.end):

tj = doc[j]

if tj.text in QUOTE_CHARS:

# reached closing quote

text = " ".join(tok.text for tok in inner_tokens).strip()

# strip trailing punctuation commonly inside quotes

while text.endswith((",", ";", ":")):

text = text[:-1].rstrip()

return text or None

inner_tokens.append(tj)

return None # no closing quote found

# 1) If rv has a colon punct child, prefer the first quoted span to the right

has_colon = any(c.dep_ == "punct" and c.text == ":" for c in rv.children)

if has_colon:

q = first_quoted_span(tokens_right_of(rv))

if q:

return q

# 2) Otherwise, still try the first quoted span to the right

q = first_quoted_span(tokens_right_of(rv))

if q:

return q

# 3) Last resort: try around explicit content heads (ccomp/parataxis),

# looking for quotes that bracket those heads.

heads = [c for c in rv.children if c.dep_ in {"ccomp", "parataxis"}]

for h in sorted(heads, key=lambda t: t.i):

# scan left from head to find the nearest opening quote

left_q = None

for i in range(h.i, sent.start - 1, -1):

if doc[i].text in QUOTE_CHARS:

left_q = i

break

if left_q is None:

continue

# scan right from head to find the nearest closing quote

right_q = None

for j in range(h.i, sent.end):

if doc[j].text in QUOTE_CHARS and j > left_q:

right_q = j

break

if right_q is not None and right_q > left_q + 1:

inner = doc[left_q + 1:right_q].text.strip()

while inner.endswith((",", ";", ":")):

inner = inner[:-1].rstrip()

if inner:

return inner

return None

def extract_speech_events(sent):

doc = sent.doc

events = []

# Step 1: find reporting heads in this sentence

reporting_heads = [t for t in sent if is_reporting_head(t)]

# Step 2: process them in left-to-right order, grouping simple conj chains

visited = set()

for head in sorted(reporting_heads, key=lambda t: t.i):

if head.i in visited:

continue

# Collect this head and any conj-linked reporting verbs into an ordered group

group = []

stack = [head]

seen_local = set()

while stack:

cur = stack.pop()

if cur.i in seen_local:

continue

seen_local.add(cur.i)

if cur in reporting_heads:

group.append(cur)

# Add conj children that are also reporting heads

for c in cur.children:

if c.dep_ == "conj" and c in reporting_heads:

stack.append(c)

# Also consider the head if current is a conj

if cur.dep_ == "conj" and cur.head in reporting_heads:

stack.append(cur.head)

group = sorted(group, key=lambda t: t.i)

for g in group:

visited.add(g.i)

# Step 3: extract events for each reporting verb in the group

for rv in group:

verb_norm = normalize_reporting_verb(rv)

speaker = get_speaker(rv)

quote_text = get_quote_for_reporting_verb(rv)

events.append({

"verb_lemma": verb_norm,

"verb_text": rv.text,

"speaker": speaker,

"quote": quote_text

})

return events

and then comes our example sentence:

text = '"Kapıyı aç," dedi dede; Keloğlan cevap verdi: "Tamam".'

doc = nlp(text)

for sent in doc.sents:

evs = extract_speech_events(sent)

for e in evs:

print(e)

With this extractor in place, we can reliably turn “Kim dedi neyi?” trees into clean speaker–quote pairs; let’s park the tooling here and shift to the next layer of structure—how subordination (ki, diye, -ince/-ken) reshapes these narratives beyond simple chains.

Wrapping up: we’ve looked at two core discourse moves in Turkish—clause chaining/parataxis and direct‑speech attribution—and showed how to operationalize both with spaCy’s Turkish models. With a few dependency cues (conj/cc for chains, ccomp/parataxis plus quote punctuation for speech) and a small, curated lexicon of reporting verbs, you can turn raw sentences into structured events: action sequences, speaker–quote pairs, and clean spans ready for downstream analysis. The takeaway isn’t just linguistic: spaCy’s tokenization, sentence segmentation, and dependency parses are stable enough to support rule-based extractors that are simple, fast, and transparent. In the next section, I’ll build on this foundation—extending the patterns to diye/ki subordination and evaluating model behavior across tr_core_news_sm/md/lg—so you can decide what’s “good enough” for your pipeline and where custom components or retagging make the biggest difference.