Natural Language Processing (NLP) has grown leaps and bounds in the past decade, but if you’re working with Turkish, you’ve probably faced some challenges. Turkish is a morphologically rich, agglutinative language that doesn’t always play nicely with NLP tools designed for English or other Indo-European languages. That’s where spaCy Turkish models come in! Whether you’re analyzing text, identifying parts of speech (POS), or parsing syntax, spaCy’s tr_core_news models are your go-to tools for Turkish NLP. In this blog, we’ll introduce you to spaCy’s Turkish models, walk you through their features, and show how to load and use them effectively. By the end, you’ll be ready to unlock the potential of Turkish texts with spaCy!

If you’ve ever played with Turkish text, you know it can be delightfully expressive—and occasionally a handful. Those stacked suffixes, long word forms, and subtle grammatical cues are part of the charm, but they can leave generic NLP tools scratching their heads. That’s why spaCy’s Turkish models exist: to make Turkish feel like a first-class citizen in your pipeline. In this post, we’ll keep the intro warm and welcoming, then glide into the nitty-gritty of the tagging schemes—morphological features, dependency labels, POS tags, and finally NER—so you know exactly what you’re getting and how to use it with confidence.

A quick note on the models (and why they work well for Turkish)

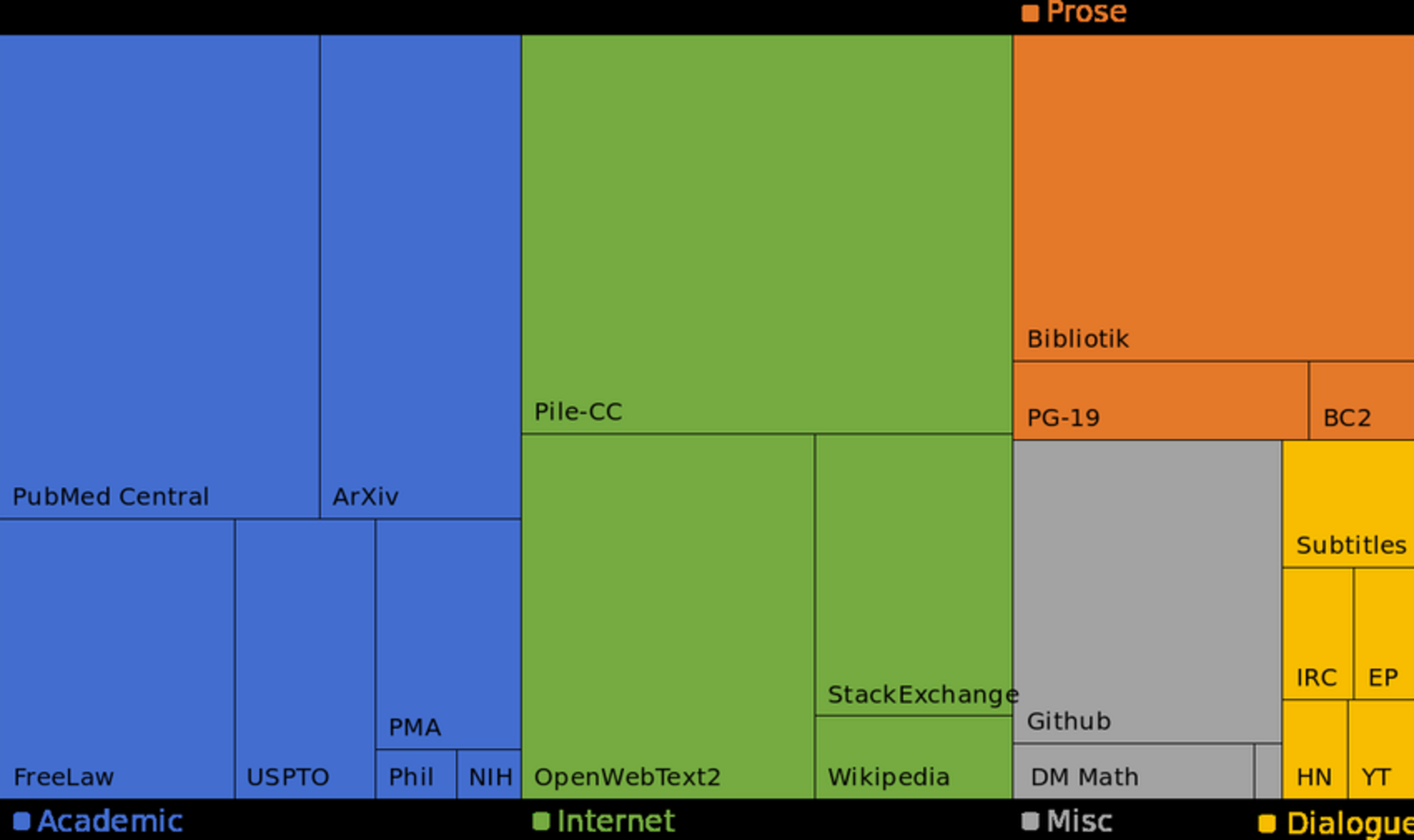

- Pipelines:

tr_core_news_md (fast, compact), tr_core_news_lg (stronger accuracy), tr_core_news_trf (Transformer, best accuracy—GPU recommended). - Components: tokenizer, POS tagger, morphologizer, trainable lemmatizer, dependency parser, NER.

- Training data: UD Turkish-BOUN for POS/morphology/dependencies/lemmas; Turkish WikiNER for entities. Design choices for Turkish:

- Subword-aware representations (Transformer WordPiece; Floret vectors in CNN models).

- UD-aligned annotations so morphology, syntax, and lemmas agree.

- Proper-name apostrophes kept in the token orthography; lemma + morph features expose the base form and grammar.

We already got to know the packages in the Medium post. The aim of this post is to get to know the training data and tagsets better. Now, let’s dive into the tagging schemes—what each layer means, how it’s annotated, and how to make it work for you. We have a tiny intorduction to Universal Dependencies though.

Universal Dependencies: a shared grammar for all languages

If you’ve ever tried to compare NLP results across languages, you’ve probably felt the friction: tag sets don’t match, dependency labels mean slightly different things, and morphology lives in ad hoc formats. Universal Dependencies (UD) was created to smooth all of that out. It’s a community‑maintained framework that standardizes how we annotate parts of speech, morphological features, and syntactic relations so that English, Turkish, Finnish, and Japanese can be analyzed with a common vocabulary. The goal isn’t to erase linguistic differences—UD respects them—but to make those differences legible through a set of “universal” tags and conventions that travel well from one language to another.

What “universal” means in UD

UD organizes annotation into three coordinated layers, each with its own universal inventory. First is UPOS, the universal part‑of‑speech set. This is a fixed, language‑agnostic inventory of coarse POS categories: ADJ, ADP, ADV, AUX, CCONJ, DET, INTJ, NOUN, NUM, PART, PRON, PROPN, PUNCT, SCONJ, SYM, VERB, and X. By agreeing on these categories, UD ensures that a noun is counted as a noun everywhere you look, and that dashboards, error analyses, and baselines can be compared across languages without a translation table.

The second layer is universal morphological features. Instead of hiding grammatical information inside long wordforms or tool‑specific tags, UD exposes it as compact key–value pairs attached to each token. The feature names themselves are shared across languages—think Case, Number, Gender, Person, Tense, Aspect, Mood, Voice, Polarity, Degree, Definite, PronType, NumType, and so on—while the allowed values can include both widely used options (e.g., Case=Nom, Number=Sing) and language‑specific values when necessary. This design gives you a tidy, machine‑readable way to talk about the grammar that languages encode differently, whether via suffixes, particles, or word order.

The third layer covers universal dependency relations: standardized labels for how words connect in a sentence. You’ll see relations like nsubj for nominal subject, obj for object, iobj for indirect object, obl for oblique nominals, acl and advcl for clausal modifiers, ccomp and xcomp for clausal complements, amod and nmod for nominal modification, conj and cc for coordination, case and mark for function words, and punct for punctuation. Because these labels are shared, parse trees have comparable structure across languages even when the surface realization is quite different. UD also includes conventions for tokenization and multi‑word expressions, so the syntactic layer rests on consistent foundations.

A note on scope and flexibility

UD is intentionally coarse at the POS level and expressive in morphology and syntax. That balance keeps the universal inventory small enough to be learnable and comparable, while leaving room for languages to express their particularities via feature values and attachment choices. The guidelines evolve through community discussion, and each treebank includes a data‑driven interpretation of the standard that fits the language’s grammar. spaCy follows those conventions rather than reinventing them, which is why you’ll see the same UPOS tags and dependency labels whether you’re analyzing newswire in one language or social media in another.

UD releases annotated corpora (“treebanks”) in a simple, line‑oriented format called CoNLL‑U. Each sentence is separated by a blank line and may include metadata comments (starting with “#”). Every token appears on one line with 10 tab‑separated columns:

ID: token index (1, 2, …) or ranges for multiword tokens (e.g., 3-4)

FORM: surface form

LEMMA: base form

UPOS: universal POS tag

XPOS: language‑specific POS tag (optional; may be "_")

FEATS: UD morphological features (Name=Value|… or "_")

HEAD: syntactic head (token ID; 0 for root)

DEPREL: dependency relation to HEAD (UD label)

DEPS: enhanced dependencies (optional)

MISC: miscellaneous info (e.g., SpaceAfter=No)

Below is a toy sentence in CoNLL‑U to illustrate the fields and the universal tag sets. The content is generic and purely for format demonstration.

sent_id = demo-1

text = The committee approved the proposal.

1 The the DET _ Definite=Def|PronType=Art 2 det _ _

2 committee committee NOUN _ Number=Sing 3 nsubj _ _

3 approved approve VERB _ Mood=Ind|Tense=Past|VerbForm=Fin 0 root _ _

4 the the DET _ Definite=Def|PronType=Art 5 det _ _

5 proposal proposal NOUN _ Number=Sing 3 obj _ _

6 . . PUNCT _ _ 3 punct _ _

You can find treebanks per different languages under UD Githu repo. Each language has several treebanks (usually created by different research groups) and each treebank has its own tagset. One very famous treebank is Penn Treebank and Penn tagset.

How treebanks train spaCy

spaCy learns its models from treebanks like the ones UD publishes. The training pipeline typically looks like this:

- Tokenization alignment: spaCy reads CoNLL‑U and aligns its own tokenizer to the treebank’s token boundaries. UD’s consistent tokenization rules (including multiword token lines like “3-4” for fused forms) make this reproducible.

- POS tagging: the tagger is trained to predict UPOS (column 4). If XPOS (column 5) is present, it can optionally be used as auxiliary supervision for language‑specific fine‑grained tags, but the universal layer remains UPOS.

- Morphological features: the morphologizer learns to predict the FEATS bundle (column 6) as a set of attributes, using UD’s shared feature names and values. This turns grammatical information into structured predictions rather than opaque tags.

- Lemmatization: supervised or rule‑assisted lemmatizers are fit using the LEMMA column (3), guided by POS and FEATS so base forms are consistent with the UD analysis.

- Dependency parsing: the parser learns to predict HEAD (7) and DEPREL (8), producing UD‑style trees. Training targets are the head indices and relation labels, and evaluation uses UAS/LAS over the UD label set.

- Optional layers: NER isn’t part of UD, but can be trained from separate annotations. Because spaCy’s core layers are UD‑aligned, NER benefits from consistent tokenization and morphology.

Why this matters before language specifics

Starting with UD and CoNLL‑U gives you a stable, interoperable substrate. Your metrics—UPOS accuracy, morphological feature F1, UAS/LAS—are directly comparable to other UD‑trained systems. Your data flow is reproducible because the treebank format is simple and auditable. And when you later discuss language‑specific behavior, you can point back to the same universal inventories and file structure that readers just saw, rather than introducing a bespoke tagging scheme.

How spaCy maps to UD

spaCy’s annotation stack is designed to align cleanly with UD. When you load a UD‑aligned pipeline, the POS tagger predicts UPOS categories from the universal inventory above. The morphologizer attaches UD‑style feature bundles to tokens, using the shared feature names and permitted values from the UD guidelines. The dependency parser outputs UD relation labels between heads and dependents, following the same naming and attachment conventions used in UD treebanks. Finally, the lemmatizer is informed by POS and morphology so that base forms are recovered consistently and can be compared across datasets. In other words, the objects you interact with in spaCy—token.pos_, token.morph, token.dep_—are direct expressions of UD’s universal layers.

Now we understood the UD basics and treebanks, we’re ready to dive into Turkish treebanks and tags.

UD Turkish‑BOUN at a glance

The Turkish‑BOUN treebank is one of the main UD resources for modern Turkish. Curated by researchers at Boğaziçi University, it targets contemporary standard Turkish across diverse genres (news, web, literature excerpts), with careful attention to tokenization, morphology, and clausal structure. It follows UD v2 guidelines while encoding Turkish‑specific phenomena—agglutinative morphology, productive derivation, participles, and clitics—in a way that remains comparable cross‑lingually.

- Size and scope: tens of thousands of sentences and tokens, with periodic updates in UD releases.

- Register and sources: written Turkish with a bias toward news/editorial prose; occasional colloquial forms and loanwords appear.

- Licensing and versioning: distributed via UD releases (CoNLL‑U format), with versioned tags and GUIDELINES notes per release.

Tokenization and orthographic conventions

Turkish‑BOUN follows UD tokenization principles but adopts choices that make downstream morphology and syntax consistent:

- Proper nouns and suffixes: proper names plus case/possessive suffixes are a single token (e.g., İstanbul’a), with lemma=İstanbul and FEATS carrying Case=Dat. Apostrophes are preserved in FORM, not split into extra tokens.

- Clitics: enclitic particles like “-ki” (as a relativizer/particle) and question particle “mi/mı/mu/mü” are generally tokenized as separate tokens when they are syntactically independent; when they are orthographic clitics inside the word, tokenization follows UD guidance and BOUN’s consistency rules.

- Multiword tokens: contractions and fused forms (rare in Turkish) use the multiword token lines (e.g., 3-4) when required by UD; most Turkish writing keeps tokens morphologically transparent, so MWTs are uncommon.

- Numbers, punctuation, and abbreviations: decimal separators, percent signs, and date formats are tokenized to keep numerals intact; punctuation receives PUNCT with case/mark attachments per UD.

Morphological features: what BOUN encodes

Because Turkish is agglutinative, BOUN’s FEATS column is rich. Expect compact, compositional bundles that expose grammar directly. Common features include:

- Case: Nom, Acc, Dat, Loc, Abl, Gen, Ins, and sometimes Equ or Voc if present in sources. Case appears on nouns, pronouns, proper nouns, and nominalized verbs.

- Number: Sing, Plur.

| Person: Person=1 | 2 | 3 for agreement; possessors use Person[psor]=1 | 2 | 3 on nouns to mark possessive suffixes; likewise Number[psor] for plural possessors. |

- PronType, NumType, Definite, Reflex: used on pronouns/determiners where relevant (e.g., PronType=Prs, Dem, Int).

- Tense/Aspect/Mood (TAM): Tense=Past|Pres|Fut; Aspect=Prog|Hab|Perf where appropriate; Mood=Ind|Imp|Des|Nec|Pot|Cnd, etc., depending on morphological evidence.

| Voice: Act, Pass, Caus, Recip; Turkish voice morphology is productive and frequently annotated (e.g., Voice=Pass | Caus). |

- Polarity: Pos or Neg for negation morphology (e.g., -ma/-me).

- Evident: Nfh (non‑firsthand) where the -miş paradigm carries evidentiality; otherwise Evident=Fh/Nfh as applicable.

- VerbForm: Fin for finite forms; Part for participles; Conv for converbs (e.g., -ken, -ınca); Vnoun for verbal nouns (e.g., -mek/-ma nominalizations).

- Case on nominalizations: UD encourages carrying case on derived nominals; BOUN annotates case even when the head is a verbal noun or participle functioning nominally.

Lemmatization strategy

- Lemmas reflect dictionary base forms: verbs to infinitive stem (gitmek → lemma=git), nouns to nominative singular (öğrenciler → öğrenci).

- For proper nouns with suffixes, apostrophes do not affect lemmas (Ankara’ya → Ankara).

- Derivational morphology that changes part of speech yields lemmas appropriate to the derived category (e.g., öğretmenlik → öğretmenlik as a noun lemma; participles keep the verb lemma with VerbForm=Part capturing the derivation).

Dependency relations: Turkish‑specific attachment habits

BOUN uses the standard UD relation set but with attachment choices informed by Turkish syntax and head‑final tendencies:

- Subjects and objects: nsubj marks nominal subjects; obj marks direct objects; iobj for true indirect objects (often dative arguments in ditransitives). Case features often disambiguate roles (Acc vs Dat).

- Obliques and adpositions: Turkish postpositions are annotated with case=ADP tokens attaching to their nominal complements, and the nominal gets obl; the adposition itself takes relation case to the nominal. Case suffixes on nominals do not introduce separate tokens but are captured in FEATS; hence many oblique arguments appear as obl with Case in FEATS.

- Clausal modifiers: acl for noun‑modifying clauses, especially participial modifiers; advcl for adverbial clauses (including converbial forms -ken, -ınca).

- Complements: ccomp for clausal complements with their own subjects; xcomp for subject/control/raising complements without an overt subject (often non‑finite).

- Copula and predication: Turkish has a null/auxiliary copula paradigm. BOUN typically treats the lexical predicate as head with cop or aux attachments for copular markers or auxiliaries, per UD conventions. Predicative nominals/adjectives often head the clause with nsubj attached.

- Coordination: conj for coordinated dependents; cc for the coordinator; head is usually the first conjunct.

- Negation, question particles, and focus markers: negation affixes yield Polarity=Neg; when standalone particles occur (e.g., mı), they are PART with the appropriate dependency (often dep or discourse/advmod depending on context) per BOUN guidelines.

BOUN assigns the universal UPOS set; a few patterns are especially common:

- VERB vs AUX: main lexical verbs get VERB; auxiliary/tam markers or certain copular elements may be AUX depending on analysis; many TAM categories are expressed as suffixes, so AUX is less frequent than in periphrastic languages.

- NOUN vs PROPN: capitalized names, institutions, and places as PROPN; suffixes do not change UPOS, they change FEATS.

- ADP: postpositions (göre, kadar, için) are ADP; case suffixes are not separate tokens.

- PART: enclitic question particle (mı) and other function particles when tokenized.

- SCONJ: subordinators like çünkü, ki (when used as a subordinator rather than clitic), eğer, diye (context‑dependent).

- CCONJ: ve, veya, ya da.

Participles, converbs, and nominalizations

A hallmark of Turkish is the heavy use of non‑finite verb forms:

- Participles (VerbForm=Part): often head relative‑like modifiers with acl; they inherit verbal features (Voice, Polarity, Tense/Aspect) while functioning adjectivally.

- Converbs (VerbForm=Conv): mark adverbial subordination (advcl), typically with suffixes such as -ken, -ınca/-ince, -ip.

- Verbal nouns (VerbForm=Vnoun): behave as NOUN/VERB hybrids; in UD, they typically keep UPOS=VERB or NOUN depending on guidelines and treebank practice. In BOUN, the common practice is to keep UPOS=VERB for non‑finite forms that retain argument structure and mark syntactic role via relations and features; fully lexicalized forms are NOUN.

Common edge cases and how BOUN handles them

- Proper names with attached case: single token; lemma without suffix; Case feature holds the information.

- Quotatives and reported speech: evidential -miş annotated as Evident=Nfh in FEATS; syntactic relation remains based on clause structure.

- Light verb constructions: nominal or verbal elements combining with etmek/yapmak may appear with the lexical component as head, and the light verb attaching as aux or compound:svc depending on BOUN’s adopted convention; check release notes for specifics used in the current version.

- Code‑mixed tokens: Language of FEATS is not used; instead, tokens keep UPOS based on function; foreign proper names are PROPN; language detection is outside UD scope.

- Punctuation and headlines: PUNCT attaches to the nearest syntactic head; ellipses and dashes are normalized; telegraphic headlines still receive UD relations as available.

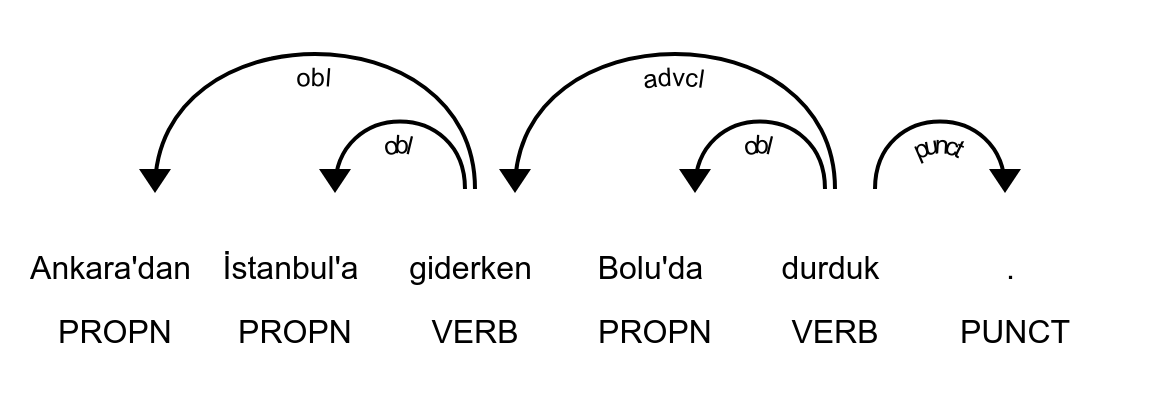

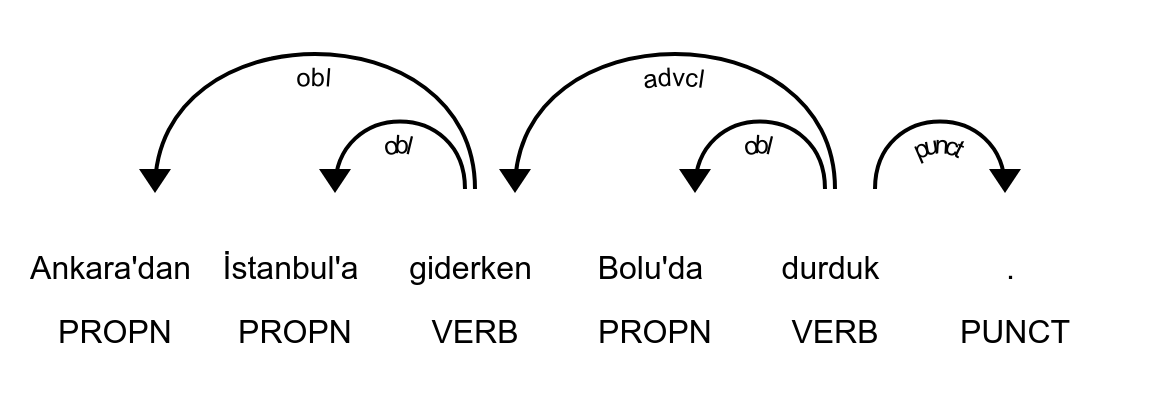

A compact, illustrative CoNLL‑U snippet

This demonstrates BOUN‑style annotations without going deep into any one phenomenon.

# sent_id = 1

# text = Ankara'dan İstanbul'a giderken Bolu'da durduk.

1 Ankara'dan Ankara PROPN Prop Case=Abl|Number=Sing 3 obl _ _

2 İstanbul'a İstanbul PROPN Prop Case=Dat|Number=Sing 3 obl _ _

3 giderken git VERB Verb VerbForm=Conv 5 advcl _ _

4 Bolu'da Bolu PROPN Prop Case=Loc|Number=Sing 5 obl _ _

5 durduk dur VERB Verb Mood=Ind|Tense=Past|VerbForm=Fin|Person=1|Number=Plur 0 root _ _

6 . . PUNCT Punc _ 5 punct _ _

We wait a moment to read this sentence. We’ll now move onto the details of how all these comes together for spaCy Turkish models, then read this sentence again:

spaCy’s Turkish pipelines are trained on UD treebanks like Turkish‑BOUN. During training, spaCy reads CoNLL‑U and learns to predict:

- pos_ = UPOS (universal POS)

- morph = FEATS (morphological features such as Case, Number, Person, Tense, Aspect, Mood, Voice, Polarity, Evident, VerbForm, possessives)

- lemma_ = LEMMA (dictionary base)

- dep_ and heads = UD dependency relations and attachments

- tag_ = language‑specific POS (XPOS). For BOUN, this is typically a minimal set mirroring UPOS (e.g., Verb, Prop, Punc) because BOUN encodes detail in FEATS rather than a rich XPOS inventory.

Training flow (BOUN → spaCy)

- Tokenization: BOUN’s choices (e.g., proper nouns with suffixes as single tokens) are preserved. spaCy’s Turkish tokenizer is configured to keep apostrophe‑joined suffixes inside the token (Ankara’dan).

- UPOS (pos_): The tagger learns the universal classes (NOUN, VERB, ADJ, PROPN, etc.).

| FEATS (morph): The morphologizer learns attribute bundles (e.g., Case=Abl | Number=Sing; for verbs, VerbForm=Fin | Tense=Past | Person=1 | Number=Plur). |

- Lemmata: Learned via rules + supervision; crucial for agglutinative stripping (İstanbul’a → İstanbul; durduk → dur).

- Dependencies: The parser learns Turkish‑specific attachments: obliques for case‑marked arguments, advcl for converbs, acl for participles, copular structures headed by the lexical predicate, postpositions as ADP with case, etc.

- XPOS (tag_): Because UD‑Turkish relies on FEATS, BOUN’s XPOS is minimal; spaCy exposes it as token.tag_. Fine‑grained distinctions live in token.morph rather than tag_.

tag_ vs pos_ in Turkish

- pos_ (UPOS): Cross‑lingual, coarse category. Examples: PROPN, NOUN, VERB, ADJ, ADV, ADP, PUNCT.

- tag_ (XPOS): Language‑specific. In BOUN‑based Turkish models, it’s often:

- Prop for proper nouns (mirrors PROPN)

- Noun for nouns, Verb for verbs, Adj for adjectives, Adv for adverbs, Punc for punctuation, etc.

- It typically does NOT encode case, TAM, voice, polarity, or possessive features. Those are in token.morph.

| Practical takeaway: Use pos_ for coarse class, token.morph for Turkish‑specific detail. Use tag_ only if you need the treebank’s native minimal labels. If you want a fine‑grained “Turkish tag,” compose it: f”{pos_} | {morph}”. |

Now we come to our example sentence again: Ankara'dan İstanbul'a giderken Bolu'da durduk. Here’s the output from the following code:

>>> doc = nlp(sentence)

>>> for token in doc:

... token, token.pos_, token.tag_, token.lemma_, token.dep_, token.head_

...

(Ankara'dan, 'PROPN', 'Prop', 'Ankara', 'obl', giderken)

(İstanbul'a, 'PROPN', 'Prop', 'İstanbul', 'obl', giderken)

(giderken, 'VERB', 'Verb', 'gider', 'advcl', durduk)

(Bolu'da, 'PROPN', 'Prop', 'Bolu', 'obl', durduk)

(durduk, 'VERB', 'Verb', 'dur', 'ROOT', durduk)

(., 'PUNCT', 'Punc', '.', 'punct', durduk)

How to read these then? First have a look at the figure above, the dependency tree of the sentence generated by displaCy. Here is an explanation token by token:

Ankara'dan

UPOS (pos_): PROPN — proper noun.

XPOS (tag_): Prop — minimal, language-specific label mirroring PROPN.

Lemma: Ankara — bare form; the suffixes are not part of the lemma.

Dependency: obl → head=giderken — an oblique argument of the going event (source).

Morphology (FEATS): Case=Abl | Number=Sing

Case=Abl: Ablative case marked by -dan/-den ("from"), signaling source/origin.

Number=Sing: Proper names are singular by default.

İstanbul'a

UPOS: PROPN

XPOS: Prop

Lemma: İstanbul

Dependency: obl → head=giderken — oblique argument (goal).

Morphology: Case=Dat | Number=Sing

Case=Dat: Dative -a/-e ("to"), signaling destination/goal of motion.

Number=Sing: Proper name in singular.

giderken

UPOS: VERB

XPOS: Verb

Lemma: git (some pipelines may surface "gider"; UD typically uses the dictionary base "git")

Dependency: advcl → head=durduk — adverbial clause modifying the main predicate.

Morphology: VerbForm=Conv (and sometimes additional features depending on the treebank)

VerbForm=Conv: Converb (non-finite adverbial verb form). The suffix -ken expresses "while V‑ing".

Why no tense/person here? Converbs are non-finite; TAM/person agreement lives on finite verbs. The -ken form typically doesn't carry person/number.

Attention: VerbForm is the key to Turkish non-finites. Recognizing converbs (Conv), participles (Part), and verbal nouns (Vnoun) lets you distinguish clausal modifiers (advcl), adjectival clauses (acl), and nominalizations (obj/nsubj as needed).

Bolu'da

UPOS: PROPN

XPOS: Prop

Lemma: Bolu

Dependency: obl → head=durduk — oblique location of the stopping event.

Morphology: Case=Loc | Number=Sing

Case=Loc: Locative -da/-de ("in/at/on"), signaling location.

durduk

UPOS: VERB

XPOS: Verb

Lemma: dur — dictionary base "to stop."

Dependency: root — head of the clause.

Morphology: VerbForm=Fin | Mood=Ind | Tense=Past | Person=1 | Number=Plur

VerbForm=Fin: Finite verb (it carries agreement/TAM and can head a clause).

Mood=Ind: Indicative mood (plain statement).

Tense=Past: Past time reference signaled by -di/-dı/-du/-dü allomorphs (here folded into -duk).

Person=1, Number=Plur: Agreement suffix -k/-k(ız) patterns; here "-uk" encodes 1PL "we."

Now that we’ve grounded how UD Turkish‑BOUN features surface in spaCy (pos_, tag_, morph, dep_, lemma_), we can move up the stack from grammatical form to semantic labels. Named Entity Recognition (NER) complements POS/morphology by identifying and categorizing real‑world mentions like people, locations, organizations, dates, and more. In Turkish, accurate NER benefits directly from the analyses you’ve seen:

- Proper names with attached case suffixes remain single tokens, so entity spans like “Ankara’dan” still resolve to the lemma “Ankara.”

- Case features (e.g., Case=Abl/Dat/Loc) help distinguish roles without breaking entity boundaries.

- Dependency cues (obl, nmod, appos) and non‑finite markers (VerbForm=Conv/Part) provide syntactic context that improves entity disambiguation.

Next, we’ll look at spaCy’s Turkish NER tags: what label set is used, how entities are segmented despite suffixes and apostrophes, and how to interpret typical labels (e.g., PERSON, LOC, ORG, GPE, DATE) on real examples.

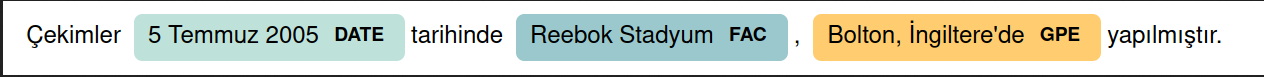

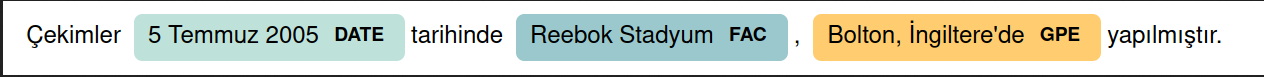

spaCy Turkish models’ NER layer is built on your professionally annotated WikiNER dataset, using a rich, modern tagset that covers both classic and fine-grained categories: PERSON, ORG, GPE/LOC, NORP, and TITLE for people and affiliations; FAC, PRODUCT, WORK_OF_ART, EVENT, and LAW for named objects and cultural items; DATE, TIME, durations like QUANTITY, ORDINAL, CARDINAL, MONEY, and PERCENT for numerics; plus LANGUAGE to capture mentions like “Türkçe.” In spaCy, these labels sit on top of the UD-informed pipeline: proper nouns with suffixes remain intact spans (e.g., “Ankara’dan” → GPE with lemma Ankara), and morphological/dependency context helps disambiguate roles without fragmenting entities. The result is a high-coverage Turkish NER system whose labels align with widely used ontologies while remaining faithful to Turkish orthography and morphology. The first picture of the page exhibits named entities of an example sentence.

That’s a wrap! We connected UD Turkish‑BOUN analyses to spaCy’s Turkish pipeline and then bridged up to your WikiNER-based NER layer with its rich label set. With pos_, tag_, morph, dep_, and high‑quality entity tags working together, you’ve got a transparent, extensible foundation for Turkish NLP at both syntactic and semantic levels. Thanks for the collaboration—feel free to reach out when you’re ready to iterate on models, expand labels, or explore evaluation and deployment. Görüşmek üzere!